Appellate Practice (Part 2)

C. Interlocutory, Discretionary (Plenary) or Direct Appeal?

Court insiders attest that interlocutory and discretionary appeals do not get the same amount of time and attention as direct appeals. It is thus essential to make a compelling argument within the self-contained application in order to have a chance. If the petition is granted, however, it will be handled in the same manner as a direct appeal.

1. Interlocutory Appeals.

Appeals prior to a final judgment are allowed only when the trial judge, within ten days of the contested order certifies “that the order, decision, or judgment is of such importance to the case that an immediate review should be had.”[65] It is still an uphill battle to get an interlocutory appeal considered. Within ten days after entry of a certificate for immediate review, the notice of appeal must be filed.[66] The time for the notice of appeal may be extended up to 30 days by the trial court.[67] Applications for an interlocutory appeal are granted only when it appears from the documents submitted that: (1) The issue to be decided appears to be dispositive of the case; (2) the order appears erroneous and will probably cause a substantial error at trial or will adversely affect the rights of the appealing party until entry of final judgment in which case the appeal will be expedited; (3) the establishment of precedent is desirable

Rule 30 (b) states that the applicant bears the burden of persuading the Court that the application should be granted. Rule 30 (d) prohibits the Clerk from accepting an application unless the filing fee is paid or an exception permits nonpayment. It also provides that the filing date is the date the application is received in conformity with court rules and payment of fees. Rule 30 (g) (1) & (2) provides specific guidance for e-filing applications and paper-filed applications. Failure to follow the detailed guidance contained in the rule may result in the application being dismissed or returned for preparation in accordance with Court rules… Court of Appeals Rule 30(a).

There is little time for consideration as the court must grant or deny an application for interlocutory appeal within 45 days. O.C.G.A. § 5-6-34(b). That time limit requires that an application for interlocutory appeal concisely and persuasively focus on these criteria, driving home not only that the trial court erred but there will be a terribly unjust result unless the Court of Appeals immediately sets it right, or that judicial economy truly requires granting the application.

a. Discretionary (Plenary) Appeal.

O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35(a) lists categories cases requiring application for appeal. These include: Appeals in cases that themselves are de novo appeals from earlier trials in magistrate court (O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35(a)(1), (11)); domestic relations appeals (O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35(a)(2), (12), except O.C.G.A. § 5-6-34(a)(11)); judgments awarding $10,000 or less (O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35(a)(6)) and awards of fees under OCGA § 9-15-14 (O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35(a)(10)). While commonly referred to as “discretionary appeals,” this is a misnomer at the appellate courts do not have discretion to deny an appeal where reversible error exists. The task for appellant’s counsel in the application for discretionary appeal is to persuade the court that there is reversible error.

Rule 31 (b) adds the requirement that the applicant bears the burden of persuading the Court that the application should be granted. Rule 31 (b) (3) & (4) adds two additional rationales for the Court to accept a discretionary application, i.e., that the “further development of the common law, particularly in divorce cases, is desirable” and that the application is for leave to appeal a judgment and decree of divorce that is final under O.C.G.A. § 5-6-34 (a) (1), timely under O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35 (d), and determined to have possible merit. If a discretionary application is filed under this rationale, it must include a certificate of good faith stating that the application has merit. If the application is found to be frivolous, the party may be sanctioned. Rule 30(d) and 30(g)(1) are similar to 30(d) and 30(g)(1) regarding payment of fees, e-filing and word count limits. It also prohibits exceeding 100 pages of exhibits (combined) unless there is a signed certificate of good faith that states, among other things, that the additional documents are necessary to apprise the Court of the appellate issues. Exempted from the 100-page limit are the application brief, application index, trial court order, certificate of immediate review, and motions with supporting documents. Also, if documents are uploaded that are deemed unnecessary or contain duplicative exhibits, the party may be sanctioned. Failure to follow the detailed guidance contained in the rule may result in the application being dismissed or returned for preparation in accordance with Court rules. Rule 31 (i) informs that extensions of time to file a discretionary application must be made via Rule 40 (b) and clarifies that filing the Rule 40 (b) motion and the later applications are separate actions, each requiring separate filing fees.

As with interlocutory appeals, time is short. The court must grant or deny the application within thirty days, so there is little time to weigh the merits. Pro forma applications are not persuasive, so the application must include the most persuasive parts of the brief of appellant. The application must be filed in the appellate court within 30 days of the order complained of. O.C.G.A. § 5-6-35(b).

b. Direct Appeal.

If there is a final judgment in a case not subject to discretionary appeal rules, the route to appeal is a Notice of Appeal within 30 days as discussed below.

D. Time Limits.

1. Notice of appeal.

Subject to tolling during pendency of a motion for new trial and an extension of time up to 30 days, the notice of appeal is due 30 days after entry of the appealable order or judgment.[68] Rather than immediately popping out a notice of appeal, one might choose to use all the available time for preparation of the appeal brief and record without, of course, missing the deadline. A notice of cross-appeal is due 15 days after filing of the notice of appeal.[69]

2. Tolling of time limit by motion for new trial.

“When a motion for new trial, a motion in arrest of judgment, or a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict has been filed, the notice shall be filed within 30 days after the entry of the order granting, overruling, or otherwise finally disposing of the motion…”[70] However, a motion for reconsideration does not toll the time limit.

3. Preparation and filing of court record.

The burden is on the appellant to get the clerk to prepare and transmit the court record. The notice of appeal must designate whether to transmit the entire record or exclude portions. At $1.00 per page and $35 for certification, the cost of a voluminous record can be prohibitively burdensome unless the trial court approves a pauper’s affidavit.[71] The appellant has four weeks to pay for the record after receipt of the clerk’s bill, or risk dismissal of the appeal by the trial court.

Court of Appeals Rule 17 includes a new requirement for the appellant, court reporters, and court clerks to cooperate to ensure that the record is complete. Rule 18 (a) adds a requirement that the trial court clerk must certify each part of the record volume. Rule 18 (c) requires that any video or audio recording of evidence submitted to the Court include the proprietary software necessary to play the recording.

The full record may include voluminous material that is not pertinent to the issues on appeal, though the exclusion of material can be fraught with danger. The speed and efficiency of clerks varies. Therefore, it may be highly cost effective to send a paralegal who is familiar with the case to the courthouse in order to assist the clerk with assembling the record. If there are problems in the record, correct them early, before the first brief is due. Once the appellate court renders its decision, it is too late.[72]

Another sage suggestion is that lawyers get a personal copy of the record organized in notebooks with the pages numbered as record transmitted to the appellate court. One might also consider the advantages of scanning the paginated record into a searchable PDF format. Either way, a personal copy of the record saves time consuming trips to the courthouse, eases the chore of referencing page and line numbers, and is accessible at home in the middle of the night.

4. Filing of transcript.

The party responsible for filing the transcript must cause it to be filed within 30 days after the filing of: (i) the notice of appeal; or (ii) designation by appellee. That includes arrangements to pay the court reporter for producing the transcript. If the party responsible for filing fails timely to file the transcript and the trial court determines that the delay was inexcusable, unreasonable, and caused by that party, the trial court has discretion to dismiss the appeal. An appellant’s appeal may not be dismissed for failure to pay costs if the costs for preparing the record are paid within 20 business days of the appellant’s receipt of the notice of the amount of costs.[73]

Appellant’s counsel should ask the court reporter for an estimated time for completion, and promptly file a motion for extension and get an order from the court to extend the time to file the transcript. As that extended deadline approaches, follow up with the court reporter and if necessary move for an additional extension. Moreover, if a motion for new trial is filed, the pendency of that motion may be utilized to obtain the transcript.

Court of Appeals Rule 18(e) authorizes transmittal of transcripts in electronic format on compact disc. In any event, counsel should ask the court reporter to provide an electronic copy of the transcript. Most court reporters have the software to provide searchable PDF versions of transcripts. If a court reporters is not so equipped, counsel may have a paralegal scan the transcript into PDF format and upgraded versions of Adobe Acrobat® perform OCR (optical character recognition) conversion in order to do word and phrase searches of the full text. The amount of time saved in computer word searches of transcripts is critical when writing the statement of facts in an appellate brief.

5. Tolling by motion for new trial.

Trial courts seldom grant motions for new trial, but such motions can buy time for getting the record and transcript in proper order before the appeal clock starts running. Filing of a valid motion for new trial, a motion in arrest of judgment, or a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict tolls the time limit for filing the notice appeal, record and transcript.[74]

b. Extensions of Time for Filing Notice

The trial judge may grant one 30 day extension of time for filing a notice of appeal and one 15-day extension to file a notice of cross-appeal.[75] Given the amount of work involved in preparing an excellent appellate brief and the time constraints involved, immediately upon entry of an appealable order or judgment, it may be prudent to seek a consent order to obtain that additional time for preparation before other deadlines begin to cascade.

E. Content of Notice of Appeal.

The Notice of Appeal should be carefully drafted, not just copied from a form book. OCGA § 5-6-37 specifies the required content of a Notice of Appeal:

. . . The notice shall set forth the title and docket number of the case; the name of the appellant and the name and address of his attorney; a concise statement of the judgment, ruling, or order entitling the appellant to take an appeal; the court appealed to; a designation of those portions of the record to be omitted from the record on appeal; a concise statement as to why the appellate court appealed to has jurisdiction rather than the other appellate court; and, if the appeal is from a judgment of conviction in a criminal case, a brief statement of the offense and the punishment prescribed. . . . In addition, the notice shall state whether or not any transcript of evidence and proceedings is to be transmitted as a part of the record on appeal.

Evaluate each of the required elements in each case:

1. “Title and docket number of the case.” Make sure you don’t mess up the simple stuff. Every court clerk has legions of stories of lawyers filing documents with the wrong case numbers.

2. “The name of the appellant and the name and address of his attorney.” Ditto. Watch out for typographical errors in spellings, and in street, suite and zip code numbers.

3. “A concise statement of the judgment, ruling, or order entitling the appellant to take an appeal.” Draft this with precision.

4. “The court appealed to” and “a concise statement as to why the appellate court appealed to has jurisdiction rather than the other appellate court.” In light of the Appellate Procedure Reform Act, this will almost always be the Court of Appeals, but check the jurisdictional rules discussed herein and cite the correct subparagraph(s).

5. “A designation of those portions of the record to be omitted from the record on appeal.” This is where the step of sending a paralegal to assist the clerk in organizing the record can be invaluable. Rather than simply stating that “nothing shall be omitted” or on the other hand omitting too much, be precise. While some dross and immaterial documents may be omitted, include enough to fully cover all issues on appeal.

6. “If the appeal is from a judgment of conviction in a criminal case, a brief statement of the offense and the punishment prescribed.” Res ipsa loquitur.

7. “State whether or not any transcript of evidence and proceedings is to be transmitted as a part of the record on appeal.” Do not slavishly copy language from a form. Drafting of this statement should be informed by counsel’s working with the court reporter and such extension orders as may be necessary in order to obtain the transcript.

F. Calendaring and Electronic Filing in Court of Appeals.

1. Register for electronic filing and pay filing fee.

As e-filing is now mandatory for lawyers in the Court of Appeals, counsel should register in advance. To avoid a $10 convenience fee for the uploading the Brief of Appellant, also prepay the $300 filing fee for civil appeals.[76]

2. Check record and transcript to confirm appellate pagination.

Obtain the clerk’s index to the record transmitted on appeal. Make sure the page numbers assigned in the record and transcript transmitted to the Court of Appeals matches the numbers in the record below. Glitches in pagination may occur due to pages skipped or double copied in a photocopier, documents unbundled and rearranged, renumbering of pages in depositions, etc. Counsel should also check legibility of documents, photographs, etc. If exhibits are transmitted on a CD, make sure they are legible, properly organized, and in color if the original was in color. It may be useful to enter docket items and pages on a spreadsheet to reconcile anomalies in pagination. If pagination is changed, conform your copy to the court’s page numbers immediately.

3. 20 days from docketing.

From the time of docketing, counsel for the appellant has 20 days to e-file the Brief of Appellant and a request for oral argument, and to pay the $300 filing fee and $10 convenience charge if the filing fee was not prepaid.

4. Request for oral argument.

The request for oral argument, due 2o days after docketing, must be a separate document, filed with the Clerk, certifying that opposing counsel has been notified of the request and that opposing counsel desires, or does not desire, to argue orally. The request must identify the counsel who would argue, and any change of counsel shall be communicated to the Clerk as soon as practicable.[77] An extension of time to file the brief does not extend the time for requesting oral argument.[78] That must be done by a separate motion. Do not just copy a form but explain with some convincing specificity how oral presentation would aid the court in addressing the issues in the case.

5. Extension of time and extension of length.

The Court of Appeals will normally grant a motion for one or two week extension, but due to constraints of the two term rule, will seldom grant longer extensions. If variation of the page / word count limits is appropriate, that requires a separate motion and order. However, remember that brevity is the soul of wit. Both time and length extensions are best done through separate consent motions and orders.

G. Enumeration of Errors and Jurisdictional Statement.

A separate “enumeration of errors” document is no longer required. It is included in Section 2 of the Brief of Appellant.

H. Standards of Review.

Carefully evaluate the standards by which the appellate court will review rulings in the trial court. The strongest arguments before the trial court and jury may be the weakest on appeal, and vice versa. This cold analysis after the passions of trial have cooled may enable appellant’s counsel to surgically trim the potential issues down to the three or four most likely to result in reversal and, where appropriate, another “bite at the apple,” a second chance to persuade the trial court and jury. This winnowing process has been called “the hallmark of effective appellate advocacy.”[79]

The Court of Appeals website includes a page of citations summarizing standards of review in many types of rulings.[80] This list was last updated in 2001, is neither exhaustive nor up to date, and should be viewed as only a starting point for further research on Westlaw, Lexis or Fastcase, e.g., “(standard /2 review) /20 [key words for type of ruling].”

Clearly, the lower the standard of review, the greater the theoretical probability of reversal. There is little or no deference to the trial court when the standard is de novo review, e.g., motions for summary judgment, pure question of law, suppression of evidence in a criminal case, and construction of contracts. Other standards of review are tougher nuts to crack, e.g., “abuse of discretion,” “clear abuse of discretion,” “clear and manifest abuse of discretion,” “clearly erroneous,” “any evidence” to support ruling, and waiver by failure to state specific ground for objection.

In selecting the issues upon which to focus on appeal, evaluate which have the best chance of success under the applicable standards of review.

I. The Appellant’s Brief.

Appellant’s brief must be filed within 20 days after the appeal is docketed.[81] The appellant’s motion for an extension of time to file a brief and enumeration of errors must be filed before the date the documents are due or the Court may dismiss the appeal, and without such an extension the appeal may be dismissed.[82]

Thus, in order to file a well-drafted and timely brief, preparation of should begin long before the case is docketed. Usually there are prior trial court briefs and memoranda from which hurried counsel may be tempted to copy and paste. The lawyer should suppress that urge as the appellate brief is a new document addressed to a new audience, the overworked appellate judge and staff attorney to whom the case is assigned on a computer “wheel” in the clerk’s office. They are inundated with a deluge of cases, wading through hundreds of briefs written in dreary, repetitive, formulaic legal prose. Yours should be more engaging those.

1. Page and word limitations.

The Supreme Court still limits briefs to 30 pages. As e-filing is now required of attorneys, the Court of Appeals has recast this as a limitation of 8,400 words in civil case, 14,000 words in criminal cases, and 4,200 words in reply briefs.

2. Structure of the brief.

Court of Appeals Rule 25 states the minimum requirements for the structure of the appellant’s brief. The Supreme Court does not prescribe the structure but generally one would follow the same structure as in the Court of Appeals. A lawyer may add an introductory “Summary of Argument” section which some judges highly recommend, tables of contents, table of authorities and an appendix.

a. Part One.

1. Summary of Argument (optional).

Write this section last, after drafting the rest of the brief. This is where the effective advocate writes a succinct “elevator speech” about why the appellant should prevail. It is an early opportunity to engage the judge and staff attorney and provide a taste of the key facts and legal arguments developed more fully in the body of the brief. But avoid overt appeals to emotion and sympathy which are likely to backfire on appeal.

2. Statement of the Case.

Succinctly and accurately summarize the proceedings below, with citations to the record and a statement of the method by which each enumeration of error was preserved for consideration. Include exhaustive citations to volumes, parts, pages and if possible lines in the record as transmitted by the trial court.

3. Statement of Facts.

Tell the story of the case in an engaging manner, with scrupulous adherence to the evidence. One each point include detailed citations to volume, page and line of the transcript as transmitted by the trial court. Beware that the page numbering system used in transmitting the record may differ from page numbers generated by the court reporter.

This can be one of the most maddening and time-consuming aspects of preparing an appeal, but it is essential. “Appellate judges should not be expected to take pilgrimages into records in search of error without the compass of citation and argument.[83] It is the burden of the party asserting error to show it affirmatively by the record.”[84]

In both the “Statement of the Case” and the “Statement of Facts,” counsel must remember that failure to direct the court to the precise location in the record or transcript that supports an enumerated error will result in waiver of that issue. Counsel cannot expect judges and staff attorneys with overwhelming workloads to go on a scavenger hunt for material to support an argument.

b. Part Two – Enumeration of Errors.

Concisely state the specific errors to be argued in the brief. Avoid a scattershot approach, focusing on the issues most likely to result in success in light of the evidence, rulings, issues and the applicable standards of review. Do not dilute your arguments with weak arguments on a plethora of other issues. Lead with your strongest issues.

c. Part Three

1. Standard of Review.

Include a concise statement of the applicable standard of review with supporting authority for each issue presented in the brief with citation to the one best source of authority for that standard.

2. Argument and Citation of Authorities.

This is the body of the brief. Issues must be set forth in the same order in which they are listed in the Enumeration of Errors. Focus on what really matters most.

J. Appellee’s Brief.

It is good to be the appellee. Inertia is on your side. Usually there is no burden to carry. Most standards of review defer to the trial court. You have the advantage of seeing what the appellant argues and responding.

Court of Appeals Rule 23 states that the Brief of Appellee is due 40 days after docketing or 20 days after filing of the appellant’s brief, whichever is later. Part One points out material inaccuracies or incompleteness of appellant’s statement of facts. It supplements the statement of facts and provides citations to additional parts of the record or transcript. Except as controverted, appellant’s statement of facts may be accepted by this Court as true. Part Two includes any different standard of review than that claimed by appellant and sets forth the appellee’s argument and the citation of authorities.

K. Persuasion beyond the rules.

1. Write well.

Put yourself in the shoes of a judge or staff attorney whose days are filled with reading reams of turgid lawyer prose. Liven up your brief within the general bounds of civility and professionalism. Make it a jewel of clarity and style, a welcome relief for the reader. Tell an engaging story. Search out the precise words and clear illustrations to persuade the court of your position. Long before time to write your brief, immerse yourself in books on legal writing, especially the works of Bryan Garner.[85] Plan your time to allow for multiple rounds of editing and rewriting.

2. Organize before you write.

Before beginning to write, use outlines or mind maps to organize and prioritize your points and authorities. Budget your time accordingly.

3. Know your judges.

Upon docketing, each case is randomly assigned on the “wheel” in the clerk’s computer to one judge in a panel of three judges. The panel assignment is disclosed with the docketing notice but the assigned judge on the panel is not revealed. It is important to read decisions by the panel members on matters related to the issues in the case, and when appropriate cite those decisions in your brief.

The internal process within the panel remains opaque to the lawyers. Primary responsibility for each case is assigned on the “wheel” to an individual judge whose identity is not disclosed. Some judges have their judicial assistant assign each case to a staff attorney before the judge looks at it, and some reportedly do not read the briefs before a staff attorney prepares a memorandum or draft order. The degree to which judges rely upon drafting of opinions by staff attorneys varies. None of that is revealed to lawyers in the case. But if the brief refers to relevant opinions authored by each member of the panel, the assigned judge and staff attorney may see their previous work referenced.

4. Know the judges’ caseload.

The Georgia Court of Appeals has one of the highest caseloads per judge of any state intermediate appellate court in the United States. Each judge has primary responsibility for roughly four final decisions per week, plus reviewing and voting on twice as many decisions authored by other judges and a steady flow of other motions, orders, and interlocutory and discretionary applications. The pressure is further intensified by the “two term rule” which requires decisions by the end of the second term after docketing. The last days before the end of the term are thus referred to as “distress.” Lawyers should do all they can to make the court’s job easier.

5. Understand “physical precedent only.”

In citing authority, it is important to recognize the distinction between decisions that are binding authority and those that are physical precedent only. A Court of Appeals decision is “physical precedent only” if one of three judges on the panel concurs in the judgment only. Such a decision “may be cited as persuasive authority, just as foreign case law or learned treatises may be persuasive, but it is not binding law for any other case.”[86]

6. Use pinpoint cites and parenthetical summaries.

To effectively use case authority, make it easy for judges and staff attorneys to go directly to pertinent passages in cases. Pinpoint citations, which refer to a specific page of the case, efficiently direct the reader to the location of the proposition for which the case is cited. In addition, brief parenthetical summaries or direct quotes are an effective way of citing to a number of precedents without detailed discussion of each case. For example:

See Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, 344, 83 S. Ct. 792, 796-97, 9 L. Ed. 2d 799, 805 (1963) (holding that Sixth Amendment mandates the appointment of counsel at no cost to the indigent defendants charged with a crime in state courts).

7. Include a Table of Contents and Table of Authorities.

These do not count against word or page limitations and are useful to the court. Consider use of electronic hyperlinks or bookmarks with these tables. “Tables of contents, tables of citations, cover sheets and certificates of service and of compliance with the word count limit shall not be counted toward the applicable page or word count limit.”[87]

8. Consider aesthetics of your brief.

In an era of mandatory e-filing, we no longer have the option of enriching the legal printing industry with professionally typeset briefs on 60 pound rag paper, in booklet form or with blue manuscript backings. But we can be thoughtful in font selection and page layout. Court of Appeals Rule 2(c)(2) and (3) requires double spacing and a serif, proportionally spaced typeface of 14-point or larger. Sans-serif fonts may be used in headings and captions. Consider going beyond default choices of Times New Roman, which screams aesthetic apathy. Other acceptable serif fonts in Microsoft Word include:

- Georgia (used in the body of the print edition of this paper)

- Century (Century family of fonts required in U.S. Supreme Court)

- Palatino Linotype

- Garamond

- Bookman Old Style

- Constantia

- Plantaganet Cherokee

Going a step further, one may consider purchase of additional fonts specifically designed for legal documents. See, e.g., Matthew Butterick, Typography for Lawyers.[88]

9. Consider electronic bookmarks and hyperlinking to an appendix.

Though not addressed in Georgia appellate court rules, entirely optional, rare and time consuming, counsel may consider inserting electronic bookmarks and hyperlinks in an e-filed brief. Bookmarks may provide internal guidance to sections and subsections. Hyperlinks embedded in a brief may link to cases within Westlaw or Lexis, or to highlighted copies of authorities, record and transcript excerpts in an appendix.[89] While potentially a great convenience for the court, this extra step in brief preparation requires advance planning and careful time management. Plan ahead.

10. Consider inserting graphics.

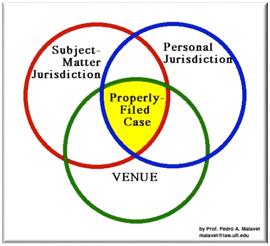

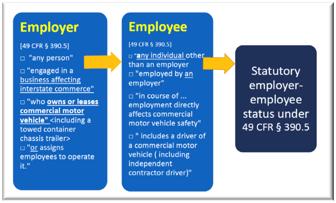

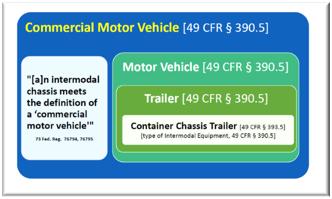

Appellate briefs traditionally are text only, perhaps referring to exhibits in the record. But persuasion can include visual elements as well. A well designed diagram may bring clarity to thousands of words of a legal argument. A few examples:

Software tools such as Microsoft Word Smartart® make it relatively easy to design insert graphics in a document, though much time and thought is required to design well. One or two key photographs from the record may be inserted as well, with reference to the record page and preferably with a hyperlink to a record excerpt in the appendix. These technical capabilities, combined with length limits expressed in word counts rather than pages, may encourage greater use of visual strategies in appellate briefs. Budget time to do this well.

11. Be concise.

Brevity requires hard work. If you can effectively tell your story in less than the word or page limits, do so. Hyperlinking and graphics may help.

12. Edit and rewrite.

You probably learned in high school that good writing requires multiple rounds of proofreading, editing and rewriting. But you won’t do that well if you push too hard on deadlines. Budget time to allow at least three days for this process.