How to Use Black Box Data in Auto Accidents

The proliferation of “black boxes” recording computer data in virtually every late-model vehicle has made our work in automobile accident lawsuits more complex and, to some extent, more subject to accurate proof.

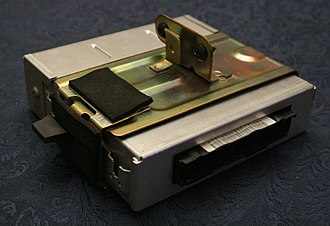

An event data recorder (EDR) or electronic control module (ECM), typically referred to as the “black box,” is a device installed in a motor vehicle to record technical vehicle and occupant information for a brief period before, during, and after a crash.

Most people have heard that after plane crashes, investigators look for the plane’s “black box” data recorder to figure out what caused the crash. What many drivers fail to realize is that cars and trucks also record significant amounts of data that can either help or hurt them in their personal injury cases. Still fewer realize that failure to preserve data after a crash can have devastating effects in a serious personal injury case.

Illustrative of the need for quick action is a case we handled a while back. The lawyer son of an Emory Law School professor signed up a case in which a gasoline tanker truck rear-ended a line of stopped cars at a red light. His professor’s father told him, “Call Ken Shigley tonight; don’t wait for morning.” We sprung into action and drafted a petition for a temporary restraining order to hold the truck in place until we could schedule a joint inspection. That inspection revealed both telematics data and a dashcam video that eliminated any argument about the cause of the fatal crash.

Although this information typically is read for seconds, those seconds worth of data can be vital in winning and losing a case. The information that is gathered from the EDR or ECM may include a vehicle’s speed and acceleration, whether airbags were deployed if breaks were applied, and if seat belts were worn. This information can be downloaded from the EDRs memory to help crash investigators, police, and others understand what happened in the vehicle, how a vehicle’s safety systems performed, and sometimes even responsibility in the crash.

Typically, EDRs are located under the passenger front seat, driver’s seat, or vehicle’s center console. Different manufacturers use different software, some proprietary and tightly controlled by the manufacturer. It is essential to employ an accident reconstructionist who is trained in the specific EDR / ECM system software.

When I attend vehicle inspections, often with the experts for both sides, they download data from a microchip onto a laptop computer by connecting a wire to a plug under the car’s dashboard, which will then generate reports for use in accident reconstruction.

There are two primary types of recorded crash events. First, a non-deployment event records data but does not deploy the airbags—it contains pre-crash and crash data; however, after 250 ignition cycles, the data is wiped out. Second, in a deployment event, airbags are deployed. The recorded data includes pre-crash and crash data, which is saved and may never be overridden.

More sophisticated modules, such as on newer large trucks, records a variety of other operational data.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) proposed rules last December that would make it mandatory for all light vehicles manufactured after September 1, 2014, to have event data recorders (EDRs) installed. Light vehicles include passenger cars, multipurpose passenger vehicles, trucks, and buses with a gross vehicle weight of 8,500 pounds or less. These new regulations could make it easier for investigators to figure out important information that led up to the event.

The NHTSA released a statement on its website saying, “EDRs can have a major impact on highway safety, assisting in real-world data collection to define the auto safety problem better, aiding in law enforcement, and understanding the specific aspects of a crash.”

EDR data can be powerful evidence in motor vehicle crash cases where liability is questioned. However, an EDR cannot be used in all crash situations. They are not completely reliable and may sometimes misread speed, airbag deployment, and seat belt use. In one of our recent cases, a tractor-trailer t-boned a passenger car, killing both people inside, but nothing of that incident was recorded on the truck’s EDR. In other cases, we have been unable to get data from an EDR that was burned beyond usefulness or left in an “off” position by the company.

Either party may challenge the admission of the EDR into evidence for the following reasons:

- The EDR was not in proper working condition and accurately recording information at the time of the accident;

- Expert testimony concerning the calibration and/ or maintenance of the vehicle;

- The EDR data is inconsistent with the damage photos, measurements at the accident scene, and testimony of witnesses.

There is a growing body of case law around the country that counsel must carefully evaluate regarding the admissibility of EDR data. Looking at the case law, lawyers seeking to use EDR data must be vigilant about laying a foundation and chain of custody for the data retrieved from an EDR, and use an expert trained to examine this data.

However, it can be expensive to have this evidence examined by an and proceed through an evidentiary hearing for the admission of the data and the proposed expert testimony. If the proper steps are taken, the evidence may be admissible and help ensure the most accurate snapshot of what actually occurred in the vehicle.

Data from an event data recorder may represent the best evidence Objective evidence from the EDR can be more reliable than eyewitnesses and traditional reconstruction as to what occurred in the seconds prior, during, and after a severe collision. However, as always, the devil is in the details, and we must never forget that while figures don’t lie, liars figure, so we have to guard against falsification and misinterpretation of EDR data.